The Social Model of Disability Explained

Edited by Stephen Braren & David Putrino, P.T., Ph.D.

Roughly one billion people—15% of the global population—experience some form of disability, according to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO). In the United States alone, about 1 in 4 adults live with a disability [1], which is defined as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities” under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In July 1990, the landmark passing of the ADA made the U.S. the first nation to ban the discrimination of people with disabilities from employment, education, health care, transportation, housing, and other areas of public life. While the ADA has undoubtedly reduced barriers for individuals with disabilities, many still face substantial obstacles to living and working fully in society. The persistence of these barriers may be largely explained by how we think and talk about disability. In particular, the question raised by some is, is a disability a medical issue rooted in the individual? Or is it more a social issue created by society?

The Medical Model of Disability

The “medical model of disability” has long informed mainstream public and professional perceptions of disability, and views disability as a problem that exists within a person’s body, only to be solved by medical doctors. This model frames the body of a person with a disability as something that needs to be “fixed,” suggesting that “typical abilities” are superior and that physical or mental impairments should be “cured” with the help of an outside force [2]. This framework, which is still embedded in modern approaches to health care and education, frames an individual’s impairment as the cause for their inability to participate fully in society.

Take for example, a wheelchair user trying to access a building’s entrance that has stairs but no ramp. According to the medical model, this person’s difficulty with entering the building is due to their mobility impairment, rather than because the building’s entrance does not have a ramp. In essence, the medical model places the burden of disability on the individual, focusing on what is 'wrong' with the person, rather than what is ‘wrong’ with the situation, context, or environment.

A consequence of the medical model of disability is that people with disabilities often report feeling socially excluded, undervalued, and treated as if they are completely incapacitated or objects of pity [3]. But for many, the main disadvantage of living with a disability is less about their own body and more about society’s response to them. This response often comes in the form of an unwelcoming reception, in terms of social attitudes and institutional norms, as well as built physical environments that promote exclusion.

The Social Model of Disability

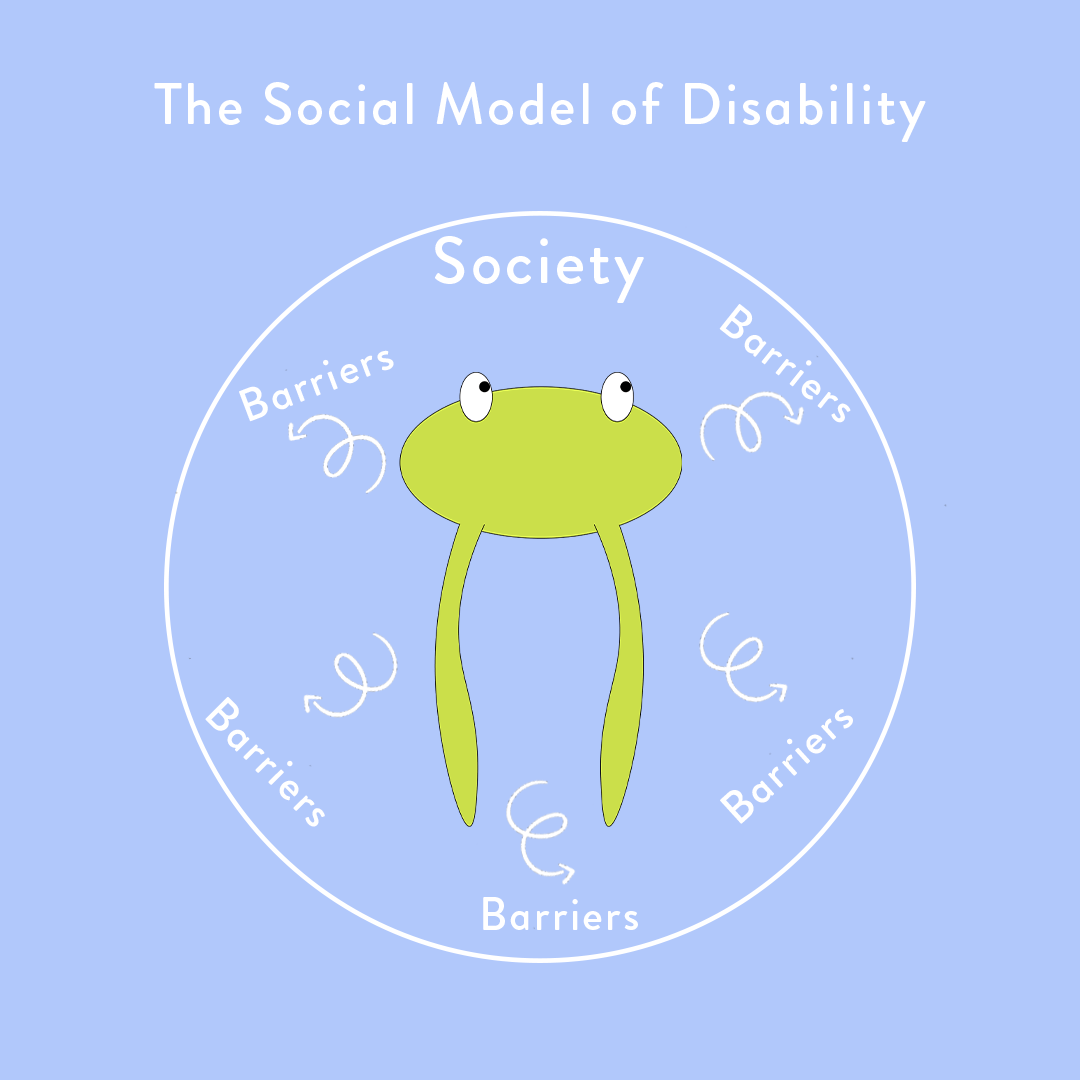

Conversely, the “social model of disability”—developed by disability rights activists in the 1970s and 80s—suggests that if societies were set up and constructed in a way that was accessible for people with disabilities, those individuals would not be restricted from full participation in the world around them. In other words, the social model of disability views the origins of disability as the mental attitudes and physical structures of society, rather than a medical condition faced by an individual.

Essentially, the social model says that individual limitations are not the cause of disability. Rather, it is society’s failure to provide appropriate services and adequately ensure that the needs of disabled people are taken into account in societal organization. Simply constructing sidewalks and entrances that are wheelchair accessible, for example, can turn a disability into an ability.

In her book What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World, Sara Hendren sums up this idea nicely: “Ability and disability may be in part about the physical state of the body, but they are also produced by the relative flexibility or rigidity of the built world … [disability] reveals just how unfinished the world really is.”

In a Forbes article titled, “We Have Been Disabled: How The Pandemic Has Proven The Social Model Of Disability,” psychologist Dr. Nancy Doyle outlines what she describes as “the responsibility that society holds for the disablement of others.” She writes, “If everyone was taught sign language at an early age, a deaf person would no longer be disadvantaged. If towns were built and planned with physical disabilities in mind and there was no social stigma attached to looking or sounding different, then having a physical impairment would no longer be disabling.”

Ultimately, the social model of disability proposes that a disability is only disabling when it prevents someone from doing what they want or need to do.

This idea changes how we typically think of disability by placing the burden of responsibility on society rather than the individual. This means that changing aspects of the built environment can change how we think about disability.

But changing how we talk about disability can also change how we think about it. The social model of disability makes an important distinction between “impairments” and “disabilities.” Impairments can be thought of as the functional limitations an individual might face (i.e., not being able to walk). Disabilities, on the other hand, are the disadvantages imposed on individuals by a society that views and treats impairments as abnormal, hence worthy of exclusion.

Physical and mental impairments are a natural and common part of being human that are deserving of accommodations and civil rights protection. They can (and frequently do) happen to anyone at any time via illness, accidents, genetic conditions, aging, and more. If sufficient accommodations are provided, however, impairments do not need to equate to disability. It is only right for society to design its physical and social infrastructure around this fact of life.

Ultimately, how a person with a disability chooses to view or talk about their impairment—whether in line with the medical model of disability or the social model of disability—is up to them. However, until we adequately examine and address society’s response to people with disabilities—including the direct role that the public’s perception of disabilities plays in creating disablement in the first place—barriers to inclusion will undoubtedly persist. And we need to remember that the barriers to more inclusive environments are not just concrete, but ingrained in our thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes. It is only when viewing disability through this lens that we can begin to change people’s perspectives on how everyday organizations and environments should be inclusively structured, and begin to actively counter the way disabled people are so commonly viewed in society: not as objects of medical treatment, charity, and tokenism or inspiration porn, but rather as full and equal members of society with human rights.

In-text references

[1] Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S. Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care Access by Disability Status and Type Among Adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:882–887. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3

[2] Goering S. Rethinking disability: the social model of disability and chronic disease. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(2):134-138. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z

[3] Mairs N. Waist-high in the world: a life among the nondisabled. Boston: Beacon; 1996.