Social Creatures Presents at the National Disability Forum

Edited by Stephen Braren

Last month, at the request of the Social Security Administration of the United States of America, Social Creatures presented at the National Disability Forum. We were asked to discuss the crisis facing children in America as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. We are reposting our National Disability Forum presentation materials in The Creature Times to amplify our messaging regarding the mental health impacts of COVID-19 on children and caregivers, as well as our recommendations for COVID-relief and recovery efforts. To check out our original presentation, along with all of the other fantastic National Disability Forum presenters’ materials, we direct you to the Social Security Administration website.

Editor’s Note: The following is a transcript of an oral presentation delivered by Dr. Rose Perry to the National Disability Forum on April 15, 2021. It has been slightly edited for clarity.

Rose Perry: Hi, I’m Rose Perry, Founder and Executive Director of Social Creatures. It’s a pleasure to be speaking with you all today.

Social Creatures is an applied research nonprofit bringing together science education, advocacy and innovation to ensure that any individual can socially connect with others, no matter the circumstances. In other words, we care about equitable social infrastructure: ensuring that everyone has access to the spaces, organizations, and services that shape their ability to socially connect and build relationships with others.

We are a highly interdisciplinary yet mission-aligned team, composed of research scientists, clinicians, educators, writers, and creatives from across the country. I myself am a social neuroscientist with a Ph.D. in Neuroscience and Physiology from New York University School of Medicine. My research has focused on the short- and long-term impacts of early life adversity on child development, with a heavy emphasis on how social connections can “get under the skin” to protect individuals from the long term, negative effects of stress and trauma.

We are a fairly young organization. We launched last April [2020] with funding from the National Science Foundation, in rapid response to COVID-19. Specifically, we were very concerned about the psychological fallout of social distancing and school closures on child and family health. So we launched with a science communication and advocacy newsletter to educate on the importance of social connection, as well as mobilized donations of computers, WiFi, and tech support to families and children without technology in the home, to help them stay connected to their school, work, and communities.

So why do we focus on social connection?

I’m sure after this past year it comes as no surprise to anyone that social connection is very important for our mental health and well being, but this is also backed by research linking social isolation to higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicide and even cognitive decline. However, what might come as more of a surprise to some of you is that social connection is also incredibly important for our physical health. Social isolation is associated with a greater risk of chronic inflammation, heart disease, and stroke. In fact, meta-analyses have shown that individuals with weak social relationships are 50% more likely to die prematurely than people with strong social relationships. So it even has been linked to our longevity.

And as the pandemic continues, Americans are facing a loneliness epidemic. A national survey in October [2020] revealed that 36% of Americans reported “serious loneliness” and this rate is nearly doubled when you look at the data for young Americans aged 18-25. These findings are thought to be linked to social distancing practices, with 88% of Americans reporting they were practicing social distancing ‘always’ or ‘very often.’ Recent meta-analyses data also indicates that quarantine heightens the risk for depression, anxiety, stress-related disorders, and anger by two to three times.

We also organized because of equity concerns, regarding how low-income households would be impacted by COVID-19, especially given that social distancing has shifted much of our lives and socialization online. And low-income households are significantly less likely to have access to computers and internet in the home. As you can see in the graph on slide six, only 54% of low-income households report owning a computer in the home vs. 94% of high-income homes.

Unfortunately, we are now starting to see statistics that low-income individuals are reporting significantly higher loneliness, stress, and worse mental health problems during COVID-19. Furthermore, low-income families are having a harder time staying connected to their communities, with 36% of low-income students reporting that they’ve had difficulties accessing school because they did not have a computer or internet in the home.

Additionally, we launched with child- and adolescent-specific concerns at front of mind. The emergence of COVID-19 in the U.S. led to school closures that impacted nearly 60 million children, disconnecting them from their peers and teachers at a developmental period where peers are of central importance, and that is critical in terms of neurodevelopment and vulnerability for the emergence of mental health disorders. Because of this we were very concerned, and remain concerned, that the social-emotional losses that children have been experiencing as a result of COVID-19 are as important if not more important than the cognitive losses.

We also can’t talk about children’s mental health without considering caregiver mental health and well being, because research has shown that stress can be readily transmitted from caregivers to their children. However, so long as parents have sufficient support and resources, they can strongly reduce or even block their child’s physiological response to stressors. So we really need to support parents to support our children.

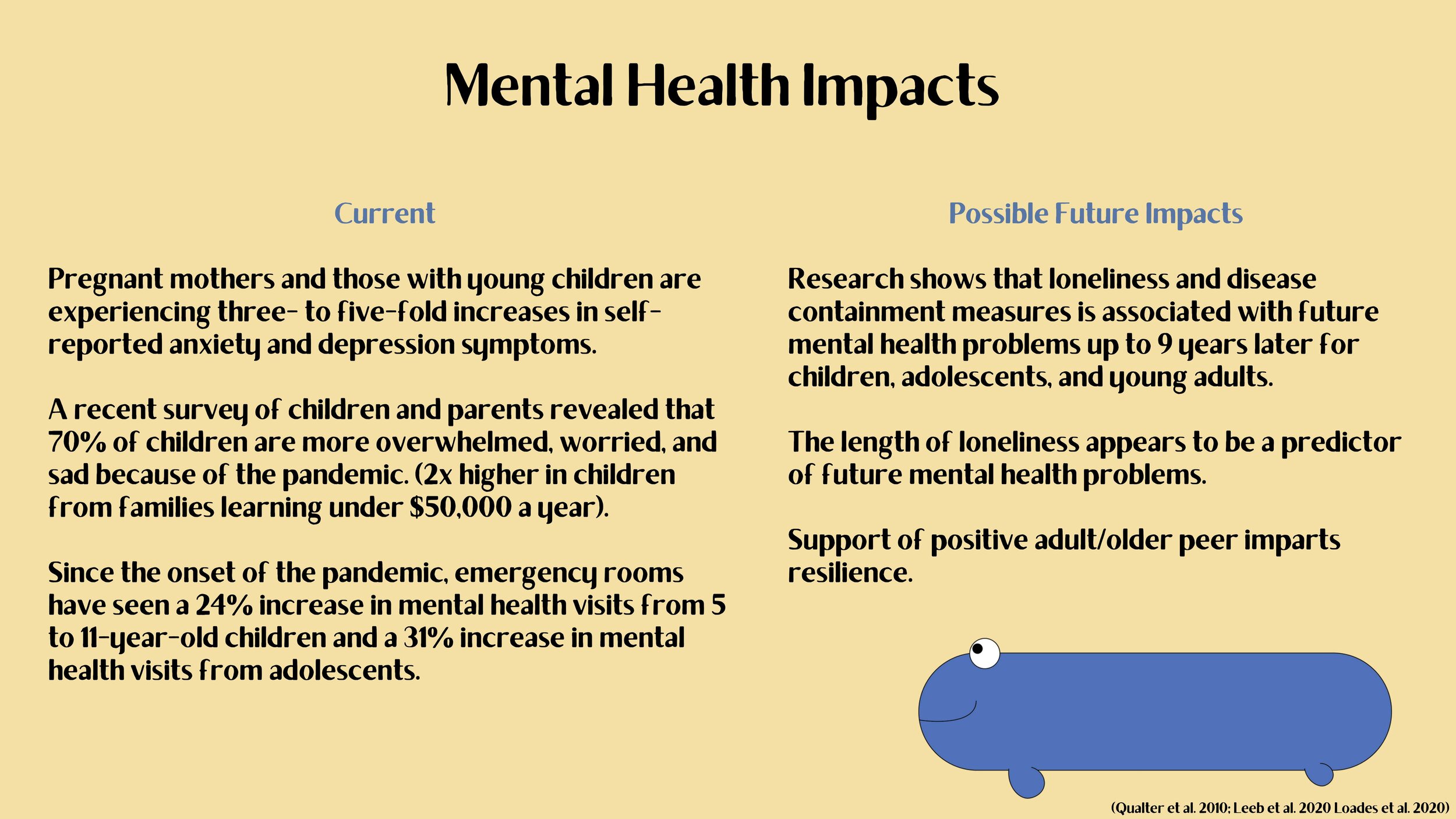

Unfortunately the pandemic has led to significant mental health impacts on children and caregivers, so we really aren’t doing enough to support them. Pregnant mothers and those with young children are experiencing three- to five-fold increases in anxiety and depression. A recent survey revealed that 70% of children are more overwhelmed, worried, and sad because of the pandemic, and this is impacting children from families earning under $50,000 a year at a disproportionately higher rate. And since the onset of the pandemic, emergency rooms have seen a 24% increase in mental health visits from five- to 11-year-olds, and a 31% increase in mental health visits from adolescents.

These statistics are also incredibly concerning in the long run if large scale supports are not provided. This is because research shows that loneliness and disease containment measures can be associated with future mental health problems for up to nine years later for children, adolescents and young adults. However, this research also provides some hope, by showing that the supportive presence of an adult or older peer helps impart resilience in the face of adversity.

At Social Creatures, we have been working hard to provide support to families and children by rapidly creating social infrastructure that enables them to safely connect with loved ones and their communities via virtual programs. We are really trying to provide support across the whole lifespan, from birth with our new parent support program, into childhood and adolescence with our Generational Youth Mentorship program, and spanning into adulthood via our Sitness seated fitness group exercise program, where our oldest participant is 93. Foundational to all of our social infrastructure programs is our Digital Safety Nets initiative, which provides the necessary technology to support our program participants’ ability to access these programs.

I want to highlight that the key to us being able to rapidly mobilize this virtual social infrastructure has been by working closely with community partners. By leveraging the trusted and established relationships that community-based organizations provide to their community members, we were able to establish swift buy-in, and ensure that we were co-designing solutions with the communities themselves.

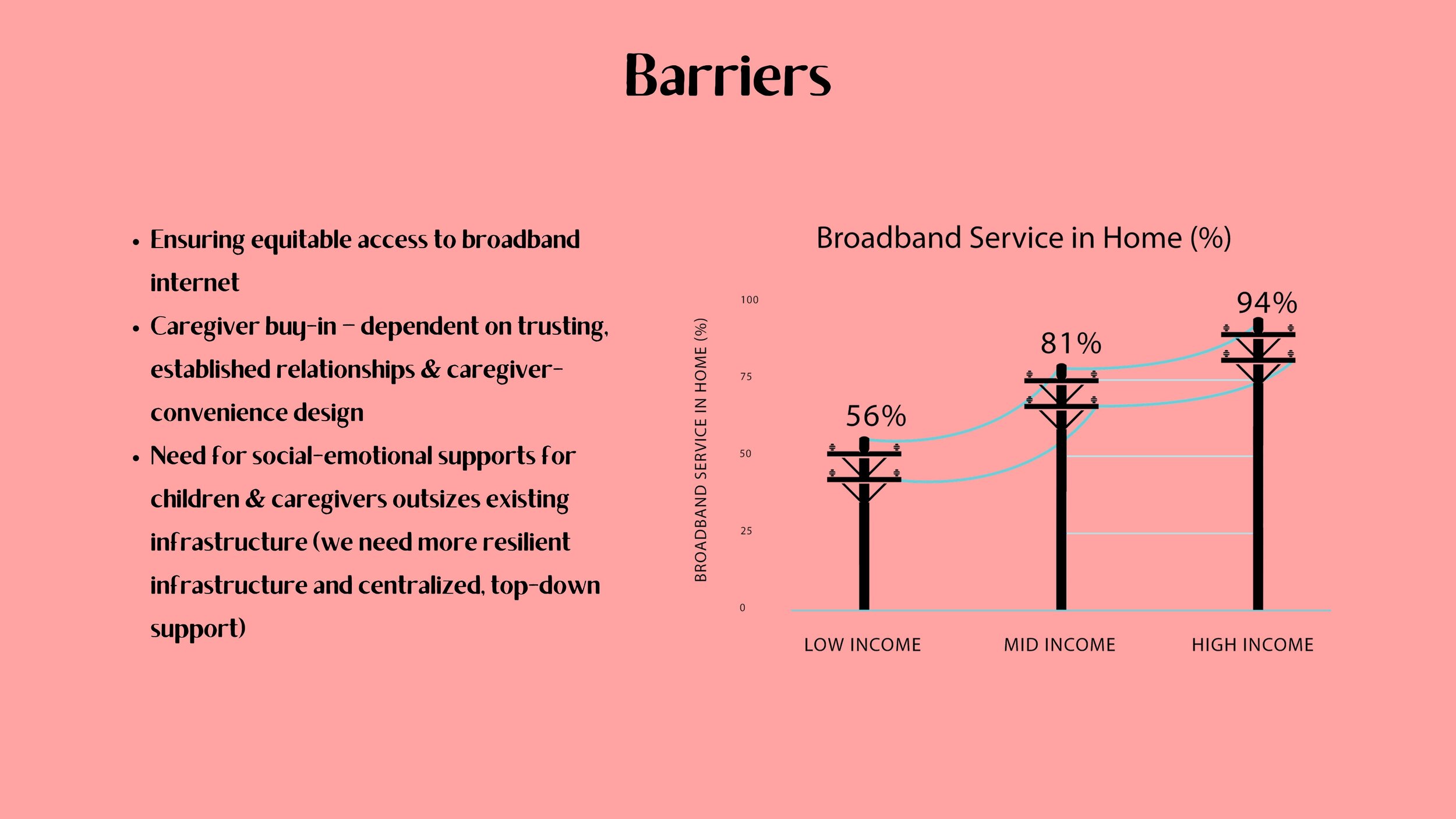

However, I also want to highlight that we’ve faced substantial barriers along the way. By far the biggest barrier that we faced and continue to face is ensuring equitable access to broadband internet. On slide 11, I have a graph showing that only 56% of low-income households have access to broadband internet versus 94% of their high-income peers. And even though major internet providers said they were opening up access in the early days of the pandemic, in reality this did not always translate to internet access for the low-income families in the communities we worked with. There were many unpublicized caveats–like if families had any outstanding debt with the companies (even if only $8) they could not setup a new account unless it was under a different adult in the household’s names, which became a nightmare to navigate for single-parent households.

Establishing caregiver buy-in for our child-focused programs was also an initial barrier, but once we really leaned in to deploying our programs through trusted community partners and designed program activities with caregiver convenience at front of mind, we were able to largely overcome this.

Finally, a huge barrier worth noting is that the need for social-emotional supports for children and caregivers that we are seeing is far outsizing the available infrastructure to support them. We need more resilient, accessible infrastructure and centralized top-down support.

Despite these barriers we’ve experienced many silver linings. COVID-19 and the shift to living our lives more online has resulted in us finally addressing longstanding inequities, with many families receiving tech in their home for the first time ever. We’ve seen that tech-enabled programming and services have made work and social lives open up to individuals with disabilities, allowing them to engage in services that were never accessible to many of them before hand. We really need to make sure these virtual, accessible options remain forever, even after in person programming resumes.

Furthermore, we are seeing that social infrastructure, even when constructed virtually, can improve social connection and quality of life, especially for historically underrepresented communities. For instance, 94% of participants in our longest running virtual program, Sitness—half of which are individuals with a disability—report that the program has improved their quality of life in the past year. I don’t know how many of you listening could say your quality of life has improved after the past year we’ve had, so I find this statistic to be incredibly powerful and revealing.

I really believe that the key to our success so far has been working closely with communities instead of for communities, to contextualize our program creation from the ground up. This led to the development of our core program design principles which I’ve listed on slide 12 for your reference. We work hard to make sure that our program inputs and activities are grounded in the science of social connection, but also incorporate Universal Design, cultural inclusivity and safety, and caregiver-forward practices that support rather than unintentionally burden our program participants and caregivers, whether they be parents, teachers or healthcare workers.

So if anything, I hope you take the following away from this talk:

That supporting the social-emotional well-being of children AND their caregivers is critical to mitigating the short- and long-term effects of COVID for children and adolescents.

That we must intentionally invest in the creation of social infrastructure, both in the physical and virtual world, to provide children and families with a multitude of ways to stay connected with their communities and loved ones, ultimately building more resilient communities.

And finally, in order to ensure that this social infrastructure is provided equitably at scale, we really require coordinated efforts merging community-led initiatives with top down support via the government and centralized policies.

To put these takeaways to work I will leave you with the following recommendations:

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of designing caregiver-forward programs and policies that are feasible, convenient, intuitive and flexible.

I also recommend lowering the barrier to entry for top-down programs and policies, via parity laws, for example, that provide equal reimbursement for virtual and in-person mental healthcare in all states.

Finally, to make sure programs and policies are benefiting everyone, we should invest in and collaborate directly with historically underrepresented communities—and this should include individuals with disabilities—to create and strengthen social infrastructure.

Thank you for your time. And thank you to the Social Creatures team who have been working around the clock for the past year. I encourage you to reach out via my email rose@thesocialcreatures.org. And you can learn more and follow along via our website and social media which I’ve listed on slide 16. Thank you!

![We are a fairly young organization. We launched last April [2020] with funding from the National Science Foundation, in rapid response to COVID-19. Specifically, we were very concerned about the psychological fallout of social distancing and school closures on child and family health. So we launched with a science communication and advocacy newsletter to educate on the importance of social connection, as well as mobilized donations of computers, WiFi, and tech support to families and children without technology in the home, to help them stay connected to their school, work, and communities.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e87430a50ddcc2ce7aa1d68/1620270416360-3AE00NQXVOVHL2BMP43I/0005.jpg)

![And as the pandemic continues, Americans are facing a loneliness epidemic. A national survey in October [2020] revealed that 36% of Americans reported “serious loneliness” and this rate is nearly doubled when you look at the data for young Americans aged 18-25. These findings are thought to be linked to social distancing practices, with 88% of Americans reporting they were practicing social distancing ‘always’ or ‘very often.’ Recent meta-analyses data also indicates that quarantine heightens the risk for depression, anxiety, stress-related disorders, and anger by two to three times.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e87430a50ddcc2ce7aa1d68/1620272668582-JSRHPSB3XX98MKER80KN/0007.jpg)